Having recently played what I identified as a “beer and pretzels” treatment of naval combat circa the Second World War, I wanted to contrast the experience with a more rigorous gaming engine. In that article I cited Steam and Iron as the best example (that I am familiar with) in PC gaming that attempts to incorporate all relevant details. The problem with this as a compare-and-contrast exercise is that Steam and Iron only covers the First World War (plus, via expansions, some of the surrounding years). Therefore, in order to look into the differences, I actually had to go back and play a scenario from the First World War.

The first naval battle of the First World War was the Battle of Heligoland Bight, a fleet action where the British force surprised the German fleet in port, ambushing their security patrols with a larger and more capable formation. Intelligence gathered via British submarines had determined that the German sentry patrols, a combination of cruisers and destroyers, were following predictable cruising patterns and a plan was devised to surprise and overwhelm those patrols.

In my mind, identifying it as the “first” neglects something obvious. In the prologue to The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman explains that she witness the true “first naval battle” of the war, albeit a bloodless engagement. The pursuit of of the battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau by more than two dozen British warships across the Mediterranean, ran for a week in early August of 1914. This too is one of the scenarios in Steam and Iron. It is a scenario I’ve played in the past but one that doesn’t suit my purpose. Without some exchanges of gunfire that actually result in serious damage and sunk ships, I really can’t compare Steam and Iron to Atlantic Fleet.

By way of contrast, I have not previously played the Heligoland Bight scenario. So it has several factors going for it; its place as the first action of the war, it being a fine exposition of large ship combat, and I’ve never played it. Perfect.

The attack plan devised by sub commander Commodore Roger Keyes was an interesting one, very much a product of that exact moment in history. Near the end of the German fleet’s night patrol, as the sun was coming up and their ships were headed home, Royal Navy submarines would show themselves and so draw the German sentries back out to sea. Unknown to the Germans, a sizable British force would use the darkness to insert themselves between the Germans and their home port and be ready to overwhelm them. Another submarine force would attempt to prevent the Germans from reinforcing the battle with a close blockade of their ports. Success required the latest technology of the time – such as those submarines, wireless communications, and the maneuverability of the oil-powered navies. It would have been foiled by yet-to-be-developed technologies (e.g. radar, improved air search, radio tracking and message intercept, etc.) that shaped otherwise similar battles during the next World War.

Alas, no plan (as they say) survives contact with the enemy.

The end-around force was spotted by a German torpedo boat before the fighting got underway. German command was alerted and began the process of “raising steam” for their modern “ships of the line,” the battlecruisers Moltke, Von der Tann, and Seydlitz as well as a number of light cruisers. It is the receipt of this alert that launches the scenario in Steam and Iron.

It’s been quite a while since I did anything with Steam and Iron and so I’m more than a little bit surprised that my installation is up to snuff. The final patch, at least for the original base game (see more explanation below), came out while I was engaged with it. Allow me now to spiral downward into some gratuitous reminiscing.

Steam and Iron is a product of the concern Naval/Tactical Warfare Simulations, aka NWS. They are a long-time producer of board games, PC games, and (maybe primarily) miniature rules. I first found out about NWS, way back when I had committed myself to a multi-year engagement with War in the Pacific, Matrix’s monster game which covers the entire Pacific theater for the entire Second World War. War in the Pacific is mostly what I’ll call “Grand Operational,” but is fairly fine grained for all that. Task forces are managed down to the individual ship level and are maneuvered on the hex board to make contact with the enemy.

From there, the details of surface combat are resolved by lining up the component ships on a tactical screen. Exchange of fire takes place* resulting in ships being sunk/damaged or until the forces disengage. The results are simplified and hands-off for the player. The experience is described as a “detailed combat animation” rather than any kind of tactical mini-game. That said, details such as guns, armor, distance, etc. as well as different categories of damage, are all part of trying to provide realism. But part of me wanted that tactical gaming experience.

Enter NWS. Their game* Warship Combat : Navies at War had an interface somewhat similar to that “animation” in WitP. Beneath the hood, though, there was far more. Their website sold the game and other NWS offerings along with discounted prices on other wargame-publishers’ products. At a time when the PC game (and wargame) industry was making the transition to digital-sales only, NWS sold the old CD jewel case for the same price as direct-from-the-publisher downloads. There is a fair chunk of my library (the HPS Sims games, for one) that was bought, at a nice discount, from NWS.

In contrast to WitP, Warship Combat : Navies at War was a fully-tactical game. The player commanded** the details of a force-on-force engagement. Furthermore, while the battle lines were portrayed linearly, the program calculated details that approximated things like ship facing, gun occlusion, and more. As far as I know Warship Combat was, in its day, the most complete computer treatment of dreadnought-era naval combat – rivaled only, perhaps, by miniatures rule sets.

While I was happily playing this game, there was much debate on-line about taking this game to a fully 2D, map-based interface. Surely that would be better? The developer at the time insisted that it would not. Because, he explained, he had managed to factor in all of the most important details, depicting the movements of the ships on a map would only detract from the realism. He may have had a point. His system tracked everything around a ship-centric frame-of-reference. The simplest, cleanest, and easiest way to present that to the user is an interface closely matching the model. Layer a map system on top of that would complicate the interface, mess up the UI, or both.

Still, we all know that a “battle board” style fight can only go so far. For one example, coastline and islands simply cannot be represented in such a linear system; it is restricted to open-ocean encouters. Eventually, NWS itself seemed to concede the point with their release Steam and Iron. Compared, graphically, to even some of its contemporaries it looks very spartan. As an upgrade to Warship Combat, it looks positively beautiful. For me, the ability to fight the battles on the map – where movements can be compared to contemporary sketches of naval actions – deepens the immersion by leaps and bounds.

So, the scenario instructions explain that 1st Heligoland Bight – 1914 (there was a 1917 engagement here as well) is designed to be confusing from a command and control standpoint. Most of your own ships are out of your control and many are out of contact. The position and count of the enemy is unknown. I played this scenario without reading up on the actual battle. All that I knew going in is what I had read, many years ago, regarding this as a precursor to the Battle of Jutland. So, honestly, I didn’t know who and what was out there in the dawn mists.

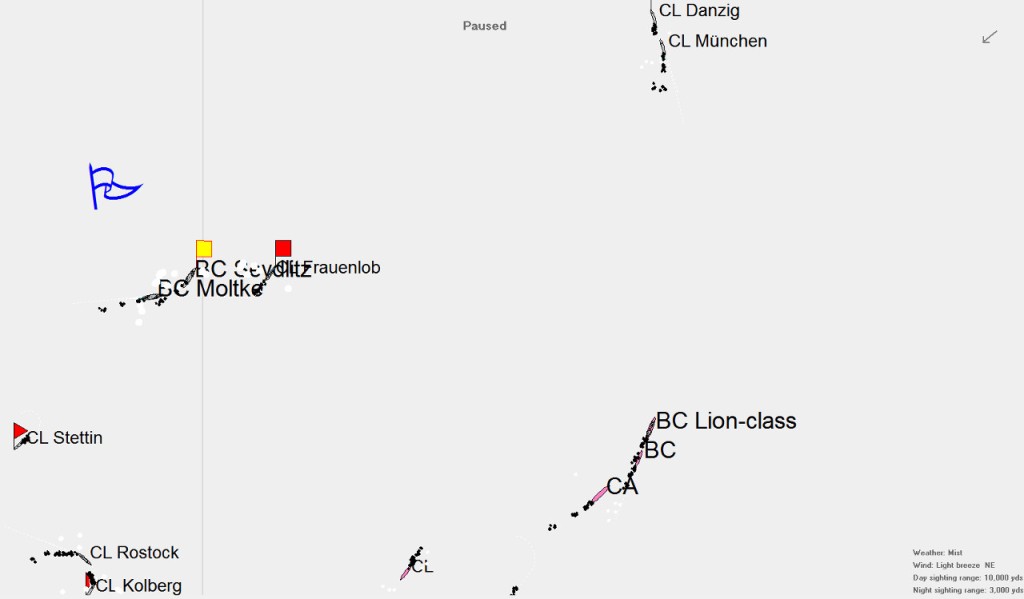

I played as Germany and the instructions for my side explain how you control very little of the force. In the above screenshot, the full extent of my command is shown by the two square flags – 2 battlecruisers and one light cruiser. That’s it. It also explains that your force will become available only gradually. “Make sure you are not beaten piecemeal, like the Germans were historically,” I was warned.

With this advice, I avoided heavy contact until I could bring my battlecruisers forward. Once in place, I tried to coordinate with the AI controlled forces to present the most potent battle line I could muster. It worked. Although I took some damage in the process, I started to see the Royal Navy battlecruisers go down. In the end (see screenshot below) I reversed history with a major victory for the Imperial German Navy.

It is tempting to write off my fairly easy win as “bad AI” or maybe to my playing using too basic a setting. As to the latter, as far as I can tell, I’ve not crippled the computer opponent in any way. As to the former, it is hard to blame the AI for this. The key is that I was playing on the “Admiral” setting which maximizes fog-of-war and minimizes own side control. Out of 41 friendlies, I had control of only three ships. Even for those three, I left the target selection, gunnery, etc. for the AI to control. My input consisted only of course and speed. If the AI was faulty, it should have affected me just as much as it did the enemy. Why, just look at the enemy battle line. He seems to be using the same strategy as me and is doing at least as well with it as I was.

So is this a game that essentially “plays itself?” In some ways it is. This can be taken either as a criticism or a complement. When one feels like a mere observer it makes one wonder what the point of even playing is. On the other hand, if the AI can competently handle both sides of a battle, it must be a sign of a well-designed AI. Either way, this also raises a further question. If the tactical battle is almost hands-free, doesn’t that beg for an operational/strategic layer on top of it to create a deeper and more meaningful game? Could this game use a “Total War treatment?”

Right around the time I stopped playing Steam and Iron, NWS was moving into this bi-level-strategy-game area. This took the form of a strategic tie-in to Steam and Iron, in the form of a campaign-level expansion, and a World War II strategic game called Supremacy at Sea. Just before I lost track, they were pushing out another game called Rule the Waves, revamping that strategic layer for the Steam and Iron time frame. Since I’ve been gone, they’ve progressed to their currently-selling Rule the Waves 2, which spans an era of naval conflict from 1900 to 1950. Per their marketing materials, this game is meant to put you at the head of your nation’s navy. You not only guide strategy and tactics but create the policies – research, design, and production – that shape the future your sea power.

I guess it goes without saying that I haven’t bought into the latter game yet. It appears to be what I really wanted play. Although the emphasis is on the strategic layer to see how variations in warship design might sway wars and battles, it also retains the tactical stuff that was the mainstay of the likes of Steam and Iron. I think I see a downloadable scenario for the Bismarck‘s attempted breakout. Maybe we’ll be back here in a few weeks (or months) to talk about all that.

One last minor point. As I was taking some of my final screenshots, including the victory screen shown above, I notice something odd. For most of the game, the fleets were drawn mostly black on white (really, very light gray). Somehow, just before the end of the game the ocean showed up as that oddly-purplish blue. What did I do? Turns out, I did nothing. In reviewing my settings, I just realized that the light, light gray is the color of fog and mist. When the fog lifted, by sea color changed to the default blue selected for oceans. What I initially took for some kind of graphics glitch was really some useful information that I had forgotten how to read.

I’ll also make one final comment about NWS, their website, and their business model. While some of the game makers for whom I regularly went to NWS are no longer selling through them, NWS still sells discounted titles. I’ve complained, both here** and before, about Atlantic Chase‘s unavailability for purchase. Between my two tirades, though, the game was put back on GMT’s P500 funding system as is now available for pre-order. NWS has its own sign-up for the pre-order available for purchase and at a 25% discount over GMT’s already-discounted pre-order price. I don’t know how he does it and still makes money off the transaction but he does. I think it is about time to renew my business relationship with NWS.

*It has been so long since I’ve played this, I’m afraid I’m getting details mixed up between games. Please forgive me if I have done so.

**One of the reasons I’m so keen on all of this right at the moment is, having been stymied in my attempt to buy Atlantic Chase, I’ve downloaded and read the manuals. That game uses a vastly simplified version of this linearized combat, reducing distance to close, medium, and far; orientation to closing, running, and acquiring; and combat to a few rounds rather than individual shots. Nonetheless, it reminds me very much of these similar, albeit far-more complex, computer solutions.

Pingback: When the Smoke had Cleared | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: Go, go, go like a Soldier | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: Arrière-ban | et tu, Bluto?