Tags

I’m working my way through some Rolling Thunder scenarios while flying the A-1 Skyraider. As I do so, I am slowly remember some things that I knew before, but had forgotten, and learning other things that I never really knew.

This is the seventy-eighth in a series of posts on the Vietnam War. See here for the previous post in the series or go back to the master post.

The Skyraider was a late World War II aircraft design; too late, in fact, to see any service during the war. It became operational only in 1946. In one sense, it was Douglas Aircraft Company’s follow-on to the SBD Dauntless, the prime carrier-based dive bomber at the start of the war and a mechanical hero at Midway. However, the design also improved upon the successes of the mid-war bombers such as the Helldiver (Curtiss SB2C).

When the Korean War started, the Skyraider was a key component of the U.S. carrier capability – U.S naval power being critical to maintaining air superiority over the Korean peninsula. The main production model circa 1950 was the AD-1, with 242 units delivered. Upgrades continued, with variants adding better engines, better defensive armor, and improved landing gear. Although it was earmarked to be replaced on carriers with a jet alternative (Grumman’s A-6 Intruder), it still remained in front-line operation at the time of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident.

By that time, the design had advanced to what was called the AD-6 which was also the A-1H, using the U.S. military’s reworked aircraft designations. This is the version that was likely to be in action in the Rolling Thunder scenarios of 1965 and early 1966. 713 A-1Hs were ultimately produced and were used by the Navy, the Marines, and the Republic of Vietnam air force.

To simply think of it as a World War II aircraft that the U.S. held on to past its prime is a mistake. The Skyraider, especially the versions fighting in Vietnam, was by no means just an upgraded Dauntless. For example, the weapons load of a Skyraider exceeded that of World War II’s B-17. The aircraft was very sturdy, with a heavily armored cockpit, earning it nicknames like “the flying dumptruck*.” While the jet age was overshadowing the propeller driven holdouts, the newer planes – and particularly the carrier-based jets – were fickle and finicky. The Skyraider was less bothered by weather, much safer in carrier operations (my experience notwithstanding), and capable of the low-and-slow attack runs that resulted in precision delivery of ordnance.

In addition to brushing up on the history, I also went through the BAT documents to try to improve my understanding in-game. It is obvious that to really enjoy the flight sim genre you need to become intimate with your plane and its capabilities, similar to what someone actually flying that plane would do. Now, I’m not saying that the two are equivalent – I’m just saying that popping open a random aircraft for a half-hour of gaming fun is necessarily going to leave a lot on the table. Getting what you can from a project as storied as this is going to involved a lot of reading.

Some of the documents that are part of the BAT installation detail the aircraft that are available. The primary focus is on the base WWII planes but there is some specific reading material for the other expansions. Unfortunately, the A-1 is not one of the planes that get this treatment and searching outside of the forum chatter, I was unable to find any specific help for my adventure. Nonetheless, the general manuals covering the Jet Age portion of the system were worth the time to read them.

One of my finds was an admonishment not to use the Autopilot key to fly missions. As the manual explains, if you fast-forward on Autopilot to skip over the boring parts and so get right to the attack phase, you’re missing out on a big piece of flying the mission. It also suggested, and I can back this up from my experience, that popping out of Autopilot right before a bombing run leaves you unready, both mechanically and mentally, to begin your attack. The time heading to the target area can and should be spent preparing for the engagement.

It also explains that there can be, inevitably, some long stretches of straight-and-level flight over the ocean that need not be experienced though real time fiddling with the throttle and stick. Instead of Autopilot, there is a “level stabilizer” function that keeps you on a straight-and-level course, but does not set the throttle nor steer to the waypoints the way that Autopilot does. It suggests that this is a better way to deal with the boring stretches while more closely approximating the modern jet’s autopilot functionality. This is all good advice. The refresher also helped me remember of some of the cockpit and HUD options.

The main thing I was searching for, however, was some help with the bombing runs. The scenario I’ve been working is a Rolling Thunder attack on a North Vietnam facility with a pretty meaty air defense setup. The scenario calls for bomb release at 3100 ft – essentially repurposing my dive bomber as a level bomber. Given the parameters of my assignment, is my plane equipped to handle such a mission?

The IL-2‘s A-1 cockpit has the MK-20 Mod 4 Gun/Bomb sight that is historically accurate for the war. It is an evolution of the WWII equipment – an adjustable site that can be used for guns, rockets, and dive-bombing. It is not useful for level bombing. In fact, from everything I’ve read (and I could, of course, be missing something important), accuracy from a flat 3100 ft in a dive bomber is just not a reasonable expectation. The fact that the AI is really good at it, while shaming me into trying harder, is probably not a realistic representation of expectations. Rather, it is an artifact of the BAT model (I think it is in BAT, at least). The AI design has non-player aircraft make perfect bomb attacks and it is up to the scenario designer to add some inaccuracy/imperfection as part of the scenario design.

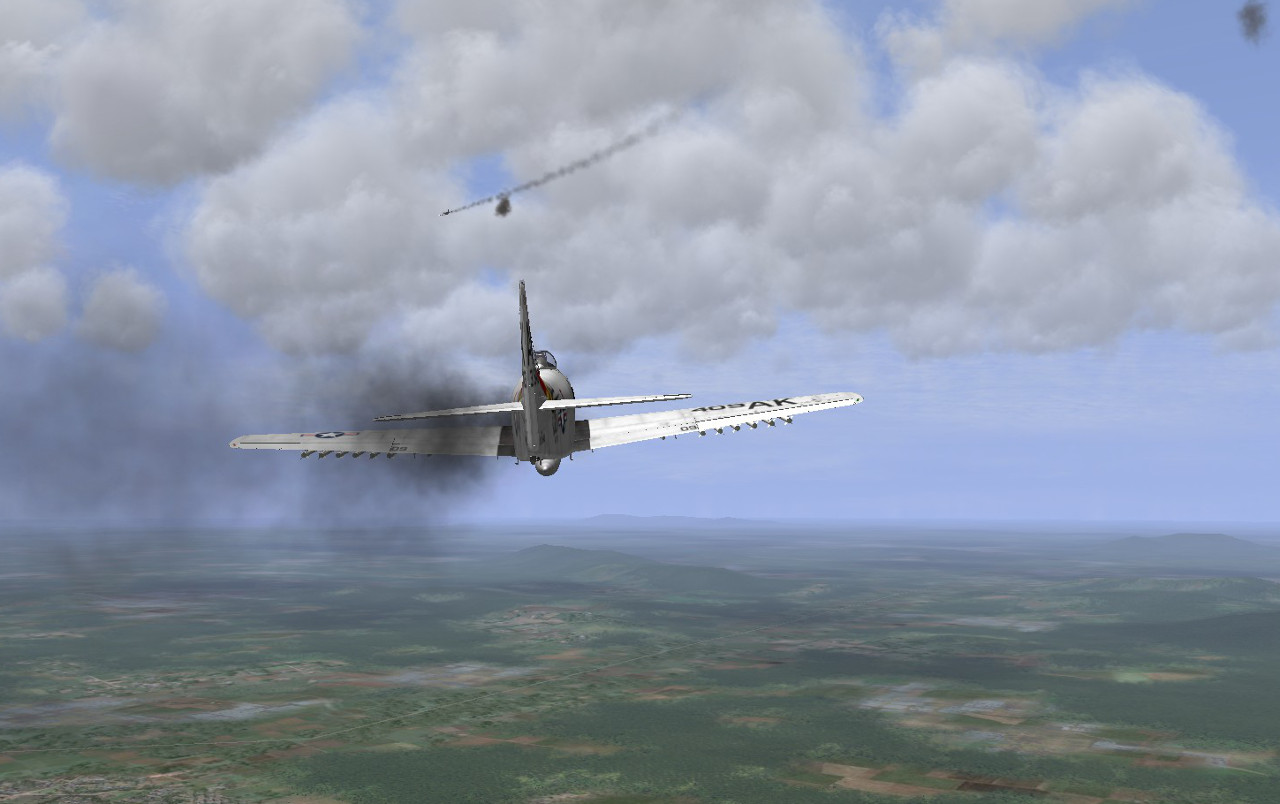

All this gave me the idea to try flying as the wingman rather than the flight leader. In this way, my super-computer enhanced leader would demonstrate when to release the bombs and I could just follow his lead. It almost worked and certainly did better than I could on my own. The release was earlier than I would have thought appropriate and so, with the AI help, I came pretty close to the target. You can see my follow up in the above screenshots where I managed to do a little damage but ultimately failed. After my flight leader took an AA hit, I came back around for a rocket attack and actually hit something – a pretty big deal for me. I ended up dying as engine damage I took during the approach finally caused my engine to fail. While I was making the turn back towards the ocean and safety, I went into a stall and then a spin. By the time I pulled the cord, I was too low to parachute out safely.

Bummer.

In the real mission, there was but one aircraft lost. During a sixth pass (!) over the target, an A-1 Skyraider was hit with anti-aircraft fire. The pilot managed to make it almost back to Da Nang air base and survived the crash landing. Contrast that to my IL-2 version where the US took multiple losses over enemy territory. In addition to my player-death, I probably had a pilot or two captured in enemy territory. I could speculate, once again, why the game is so much more lethal than reality but I think I’ll leave it be for now.

Return to the master post or go on to continue on with me and my adventures flying the Skyraider.

*I think this was actually the A-1E version, which was a two-seater, so I’m stretching the truth a little. The most common name I’ve seen in old video footage is SPAD; a mashup of the French plane used by America in the First World War and the AD designation of the aircraft. Presumably this was in reference to its throwback appearances.

Pingback: With Positive Reply | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: Giggity | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: Not Gonna Let ’em | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: Sight and Sound | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: ‘Cause I Wanna Get Carried Away | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: The Michelin Men | et tu, Bluto?

Pingback: The Straight and True | et tu, Bluto?